|

The Indian rupee (code: INR) is the official currency of India. The issuance of the currency is controlled by the Reserve Bank of India. The most commonly used symbols for the rupee are Rs., or as Re. On March 5, 2009 the Indian Government announced a contest to create a symbol for the Rupee.The Rupee is expected to get a new symbol after the Cabinet decides the final symbol. Presently, 5 symbols have been selected and out of them, one is to be finalized. The modern rupee is subdivided into 100 paise (singular paisa). The coins have a nominal value of 5, 10, 20, 25 and 50 paise as well as 1, 2, 5 and 10 rupee. The banknotes are available in a nominal value of 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 500 and 1000 rupee.

In most parts of India, the rupee is known as the rupee, rupaya (Hindi), rupiyo in Gujarati , roopayi in Telugu, Tulu and Kannada, rubai in Tamil, roopa in Malayalam, rupaye in Marathi or one of the other terms derived from the Sanskrit rupyakam;raupya meaning silver; rupyakam meaning (coin) of silver. However, in West Bengal, Tripura, Mizoram, Orissa, and Assam, the Indian rupee is officially known by names derived from the Sanskrit Tanka. Thus, the rupee is called Taka in Bengali, toka in Assamese, and Tongka in Oriya, with the symbol T, and is written as such on Indian banknotes.

On 23 June 2010, the exchange rate was Rs. 46.27 to US$1.

Numeral system

As is standard in Indian English, large values of Indian rupees are counted in terms of thousands, lakh (100 thousand = 105 rupees, in digits 100,000), crore (100 lakhs = 107 rupees, in digits 10,000,000) and arawb (100 crore = 109 rupees, in digits 1,000,000,000). The use of million or billion, as is standard in American or British English, is far less common.

For example, the amount INR 3,25,84,729.25 is spoken as three crore twenty-five lakhs eighty-four thousand seven hundred twenty-nine rupees and twenty-five paise (see Indian numbering system).

History

Use in India

India was one of the earliest issuers of coins (circa 6th century BC). The first "rupee" is believed to have been introduced by Sher Shah Suri (1486-1545), based on a ratio of 40 copper pieces (paisa) per rupee.[4] Among the earliest issues of paper rupees were those by the Bank of Hindustan (1770-1832), the General Bank of Bengal and Bihar (1773-75, established by Warren Hastings) and the Bengal Bank (1784-91), amongst others. Until 1815, the Madras Presidency also issued a currency based on the fanam, with 12 fanams equal to the rupee.

Historically, the rupee, derived from the Sanskrit word raupya, which means silver, was a silver coin. This had severe consequences in the nineteenth century, when the strongest economies in the world were on the gold standard. The discovery of vast quantities of silver in the U.S. and various European colonies resulted in a decline in the relative value of silver to gold. Suddenly the standard currency of India could not buy as much from the outside world. This event was known as "the fall of the rupee".

India was not affected by the imperial order-in-council of 1825 that attempted to introduce the British sterling coinage to the British colonies. British India at that time was controlled by the British East India Company. The silver rupee continued as the currency of India throughout the entire period of the British Raj and beyond. In 1835, British India set itself firmly upon a mono-metallic silver standard based on the rupee. His decision was influenced by a letter, written in the year 1805, by Lord Liverpool that extolled the virtues of mono-metallism.

Following the Indian Mutiny in 1857, the British government took direct control of British India. Since 1851, gold sovereigns were being produced in large numbers at the Royal Mint branch in Sydney, New South Wales. In the year 1864 in an attempt to make the British gold sovereign become the 'imperial coin', the treasuries in Bombay and Calcutta were instructed to receive gold sovereigns. These gold sovereigns however never left the vaults. As was realized in the previous decade in Canada and the next year in Hong Kong, existing habits are not easy to replace. And just as the British government had finally given up any hopes of replacing the rupee in India with the pound sterling, they simultaneously realized, and for the same reasons, that they couldn't easily replace the silver dollar in the Straits Settlements with the Indian rupee, as had been the desire of the British East India Company.

Since the great silver crisis of 1873, a growing number of nations had been adopting the gold standard. In 1898, following the recommendations of the Indian Currency Committee, British India officially adopted the gold exchange standard by pegging the rupee to the British pound sterling at a fixed value of 1 shilling 4 pence (i.e., 15 rupees = 1 pound). In 1920, the actual silver value of the rupee was increased in value to 2 shillings (10 rupees = 1 pound). In British East Africa at this time, the decision was made to replace the rupee with a florin. No such opportunity was, however, taken in British India.

In 1927, the peg was once more reduced, this time to 18 pence (13½ rupees = 1 pound). This peg was maintained until 1966, when the rupee was devalued and pegged to the U.S. dollar at a rate of 7.5 rupees = 1 dollar (at the time, the rupee became equal to 11.4 British pence). This peg lasted until the U.S. dollar devalued in 1971.

The Indian rupee replaced the Danish Indian rupee in 1845, the French Indian rupee in 1954 and the Portuguese Indian escudo in 1961. Following independence in 1947, the Indian rupee replaced all the currencies of the previously autonomous states. Some of these states had issued rupees equal to those issued by the British (such as the Travancore rupee). Other currencies included the Hyderabad rupee and the Kutch kori. Nominal value during British rule, and the first decade of independence:

- 1 damidi(pie) = 0.520833 paise

- 1 kani(pice) = 1.5625 paise

- 1 paraka = 3.125 paise

- 1 anna = 6.25 paise

- 1 beda = 12.5 paise

- 1 pavala = 25 paise

- 1 artharupee = 50 paise

- 1 rupee = 100 paise

In 1957, decimalisation occurred and the rupee was divided into 100 naye paise (Hindi for "new paise"). In 1964, the initial "naye" was dropped. Many still refer to 25, 50 and 75 paise as 4, 8 and 12 annas respectively, not unlike the usage of "bit" in American English for ½ dollar.

In March 2009 the Indian Finance Ministry launched a public competition to select a symbol for the currency.

The rupee on the East African coast and South Arabia

In East Africa, Arabia, and Mesopotamia the Rupee and its subsidiary coinage was current at various times. The usage of the Rupee in East Africa extended from Somalia in the north, to as far south as Natal. In Mozambique the British India rupees were overstamped, and in Kenya the British East Africa Company minted the rupee and its fractions as well as pice. The rise in the price of silver immediately after the First World War caused the rupee to rise in value to two shillings sterling. In 1920 in British East Africa, the opportunity was then taken to introduce a new florin coin, hence bringing the currency into line with sterling. Shortly after that, the Florin was split into two East African shillings. This assimilation to sterling did not however happen in British India itself. In Somalia the Italian colonial authority minted 'rupia' to the exact same standard, and called the pice 'besa'.

The rupee in the Straits Settlements

The Straits Settlements were originally an outlier of the British East India Company. The Spanish dollar had already taken hold in the Straits Settlements by the time the British arrived in the nineteenth century, however, the East India Company tried to introduce the rupee in its place. These attempts were resisted by the locals, and by 1867 when the British government took over direct control of the Straits Settlements from the East India Company, attempts to introduce the rupee were finally abandoned.

International use

With Partition, the Pakistani rupee came into existence, initially using Indian coins and Indian currency notes simply overstamped with "Pakistan". In previous times, the Indian rupee was an official currency of other countries, including Aden, Oman, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the Trucial States, Kenya, Tanganyika, Uganda, the Seychelles, and Mauritius.

The Indian government introduced the Gulf rupee, also known as the Persian Gulf rupee (XPGR), as a replacement for the Indian rupee for circulation exclusively outside the country with the Reserve Bank of India [Amendment] Act, 1 May 1959. This creation of a separate currency was an attempt to reduce the strain put on India's foreign reserves by gold smuggling. After India devalued the rupee on 6 June 1966, those countries still using it - Oman, Qatar, and the Trucial States (which became the United Arab Emirates in 1971) - replaced the Gulf rupee with their own currencies. Kuwait and Bahrain had already done so in 1961 and 1965 respectively.

The Bhutanese ngultrum is pegged at par with the Indian rupee, and both currencies are accepted in Bhutan. The Indian rupee is also accepted in towns in Nepal which lie near the border with India.

Coins

East India Company, -1862

The three Presidencies established by the British East India Company (Bengal, Bombay and Madras) each issued their own coinages up to 1835. All three issued rupees together with fractions down to ½ and 1/16 rupee in silver. Madras also issued 2 rupees coins.

Copper denominations were more varied. Bengal issued 1 pie, ½, 1 and 2 paise. Bombay issued 1 pie, ¼, ½, 1, 1½, 2 and 4 paise. In Madras, there were copper coins for 2, 4 pies, 1, 2 and 4 paisa, with the first two denominated as ½ and 1 dub or 1/96 and 1/48 rupee. Note that Madras also issued the Madras fanam until 1815.

All three Presidencies issued gold mohurs and fractions of mohurs, including 1/16, ½, ¼ and ½ in Bengal, 1/15 (a gold rupee) and ½ (pancia) in Bombay and ¼, ½ and ½ in Madras.

In 1835, a single coinage for the EIC was introduced. It consisted of copper 1/12, ¼ and ½ anna, silver ¼, ½ and 1 rupee and gold 1 and 2 mohurs. In 1841, silver 2 annas were added, followed by copper ½ pice in 1853. The coinage of the EIC continued to be issued until 1862, even after the Company had been taken over by the Crown.

Regal issues, 1862-1947

In 1862, coins were introduced which are referred to as Regal issues. They bore the portrait of Queen Victoria and the designation "India". Denominations were 1/12 anna, ½ pice, ¼ and ½ anna (all in copper), 2 annas, ¼, ½ and 1 rupee (silver) and 5 and 10 rupees and 1 mohur (gold). The gold denominations ceased production in 1891 while no ½ anna coins were issued dated later than 1877.

In 1906, bronze replaced copper for the lowest three denominations and in 1907, a cupro-nickel 1 anna was introduced. In 1918 and 1919, cupro-nickel 2, 4 and 8 annas were introduced, although the 4 and 8 annas coins were only issued until 1921 and did not replace their silver equivalents. Also in 1918, the Bombay mint struck gold sovereigns and 15 rupee coins identical in size to the sovereigns as an emergency measure due to the First World War.

In the early 1940s, several changes were implemented. The 1/12 anna and ½ pice ceased production, the ¼ anna was changed to a bronze, holed coin, cupro-nickel and nickel-brass ½ anna coins were introduced, nickel-brass was used to produce some 1 and 2 annas coins, and the composition of the silver coins was reduced from 91.7% to 80%. The last of the regal issues were cupro-nickel ¼, ½ and 1 rupee pieces minted in 1946 and 1947.

Independent issues, predecimal, 1950-1957

India's first coins after independence were issued in 1950. They were 1 pice, ½, 1 and 2 annas, ¼, ½ and 1 rupee denominations. The sizes and compositions were the same as the final Regal issues, except for the 1 pice, which was bronze but not holed.

Independent issues, decimal, 1957-

The first decimal issues of India consisted of 1, 2, 5, 10, 25 & 50 naye paise, as well as 1 rupee. The 1 naya paisa was bronze, the 2, 5 & 10 naye paise were cupro-nickel & the 25 & 50 naye paise & 1 rupee were nickel. In 1964, the word naya(e) was removed from all the coins. Between 1964 & 1967, aluminum 1, 2, 3, 5 & 10 paise were introduced. In 1968, nickel-brass 20 paise were introduced, replaced by aluminum coins in 1982. Between 1972 & 1975, cupro-nickel replaced nickel in the 25 & 50 paise as well as the 1 rupee. In 1982, cupro-nickel 2 rupees coins were introduced. In 1988, stainless steel 10, 25 & 50 paise were introduced, followed by 1 & 5 rupee coins in 1992. Recently 5 Rupee coins made from Brass are being minted by RBI

Between 2005 & 2008, new, lighter 50 paise, 1, 2 & 5 rupee coins were introduced, all struck in ferritic stainless steel. The move was prompted by the melting down of older coins whose face value was less than their scrap value.

The coins commonly in circulation are 1, 2, 5 & 10 rupees. Although they remain valid, paise coins have become increasingly rare in regular usage.

The coins are minted at the four locations of the India Government Mint. Note the 1, 2 & 5 rupee coins have been minted since independence. Coins minted with the "Hand Picture" are 2005 onwards.

Banknotes

British India, 1861-1947

In 1861, the Government of India introduced its first paper money, 10 rupee in 1864, 5 rupees in 1872, 10,000 rupees in 1899, 100 rupees in 1900, 50 rupees in 1905, 500 rupees in 1907 and 1000 rupees in 1909. In 1917, 1 and 2½ rupees notes were introduced.

The Reserve Bank of India began note production in 1938, issuing 2, 5, 10, 50, 100, 1000 and 10000 rupee notes, while the Government continued to issue 1 rupee notes.

Independent issues since 1949

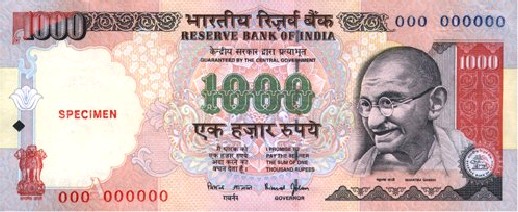

After independence, new designs were introduced to remove the portrait of the King. The government continued to issue the 1 rupee note, while the Reserve Bank issued other denominations, including the 5000 and 10,000 rupee notes introduced in 1949. In the 1970s, 20 and 50 rupee notes were introduced but denominations higher than 100 rupees were demonetized in 1978. In 1987, the 500 rupee note was introduced, followed by the 1000 rupees in 2000.

In September 2009, Reserve Bank of India has decided to introduce polymer notes (polymer banknote) on a trial basis. Initially, 100 crore (1 billion) pieces of Rs. 10 denomination notes will be introduced.According to the Reserve Bank officials, the polymer notes will have an average lifespan of 5 years (4 times the regular Indian bank notes) and be difficult to counterfeit. The polymer notes are cleaner than the regular notes, too.

Currently circulating notes

The current series, which began in 1996, is called the Mahatma Gandhi series. Currency notes are printed at the Currency Note Press, Nashik, Bank Note Press, Dewas, Bharatiya Note Mudra Nigam (P) Limited presses at Salboni and Mysore and at the Watermark Paper Manufacturing Mill, Hoshangabad.

Each banknote has its amount written in 17 languages (English & Hindi on the front, and 15 others on the back) illustrating the diversity of the country. ATMs usually give Rs. 100, Rs. 500, and Rs. 1000 notes. Rs. 1000 notes are analogous to the higher valued notes of the United States dollar and the euro.

In recent years, the banknotes were slightly modified to include see through registration on the left side of obverse. In addition, the year is now printed on the reverse. EURion constellation was added to Rs. 100. The revised Rs. 10, 20 were issued in 2006, and Rs. 50, 100, 1000 in 2005. The RS. 5 notes were stopped from being printed, but have started again since 2009.

Language panel

The language panel on Indian rupee banknotes display the denomination of the note in 15 of the 22 official languages of India.

Security features

Watermark - White side panel of notes has Mahatma Gandhi watermark.

Security thread - All notes have a silver security band with inscriptions visible when held against light which reads Bharat in Hindi and RBI in English.

Latent image - Higher denominational notes (Rupees 20 onwards) display the note's denominational value in numerals when held horizontally at eye level.

Microlettering - Numeral denominational value is visible under magnifying glass between security thread and latent image.

Fluorescence - Number panels glow under ultra-violet light.

Optically variable ink - Notes of Rs. 500 and Rs. 1000 have their numerals printed in optically variable ink. Number appears green when note is held flat but changes to blue when viewed at angle.

Back-to-back registration - Floral design printed on the front and the back of the note coincides and perfectly overlap each other when viewed against light.

EURion constellation

Convertibility

Officially, the Indian rupee has a market determined exchange rate. However, the RBI trades actively in the USD/INR currency market to impact effective exchange rates. Thus, the currency regime in place for the Indian rupee with respect to the US dollar is a de facto controlled exchange rate. This is sometimes called a dirty or managed float. Other rates such as the EUR/INR and INR/JPY have volatilities that are typical of floating exchange rates.It should be noted, however, that unlike China, successive administrations (through RBI, the central bank) have not followed a policy of pegging the INR to a specific foreign currency at a particular exchange rate. RBI intervention in currency markets is solely to deliver low volatility in the exchange rates, and not to take a view on the rate or direction of the Indian rupee in relation to other currencies.

Also affecting convertibility is a series of customs regulations restricting the import and export of rupees. Legally, foreign nationals are forbidden from importing or exporting rupees, while Indian nationals can import and export only up to 5000 rupees at a time, and the possession of 500 and 1000 rupee notes in Nepal is prohibited.

RBI also exercises a system of capital controls in addition to the intervention (through active trading) in the currency markets. On the current account, there are no currency conversion restrictions hindering buying or selling foreign exchange (though trade barriers do exist). On the capital account, foreign institutional investors have convertibility to bring money in and out of the country and buy securities (subject to certain quantitative restrictions). Local firms are able to take capital out of the country in order to expand globally. But local households are restricted in their ability to do global diversification. However, owing to an enormous expansion of the current account and the capital account, India is increasingly moving towards de facto full convertibility.

Many economist have a confusion regarding the interchange of the currency with the gold, but the system that India follows is that money cannot be exchanged for gold, in any circumstances or any situation.Money cannot be changed into gold by the RBI. This is because it will becomes difficult to handle it. India follows the same principle of Great Britain and America.

Chronology

-

1991 - India began to lift restrictions on its currency. A series of reforms remove restrictions on current account transactions including trade, interest payments & remittances and on some capital assets-based transactions. Liberalized Exchange Rate Management

System (LERMS), a dual exchange rate system, introduced a partial convertibility of the Rupee in March 1992.

- 1997 - A panel set up to explore capital account convertibility recommended India move towards full convertibility by 2000, but timetable abandoned in the wake of the 1997-98 East Asian financial crisis.

- 2006 - The Prime Minister, Dr Manmohan Singh, asks the Finance Minister and the Reserve Bank of India to prepare a road map for moving towards capital account convertibility. "The "Fuller Capital Account Convertibility Report"". 2006-07-31. http://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/PublicationReport/Pdfs/72250.pdf. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

The text on this page has been made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License and Creative Commons Licenses

|